Summary of Extinct Apex Predator Likely Weaker Than Assumed, Research Says:

Scientists have conducted thorough studies on the marine animal Anomalocaris canadensis and have found that it was likely weaker than initially assumed. The animal, previously believed to be an “apex predator,” was more agile and fast in pursuing soft prey rather than catching hard-shelled sea creatures. Researchers used 3D reconstructions and biomechanical modeling to find that the animal’s front appendages were not built for catching hard prey. The findings suggest that the dynamics of the Cambrian food webs were more complex than previously thought. Anomalocaris canadensis was one of the largest marine animals to live 508 million years ago and played a role in the explosion of diversity of life during the Cambrian period.

– New research suggests that the extinct marine animal Anomalocaris canadensis was weaker than initially believed

– Biochemical studies on the creature’s arachnid-like front legs indicate that it was more suited to pursuing soft prey rather than catching hard-shelled sea creatures

– Previous assumptions that Anomalocaris was an apex predator are being challenged

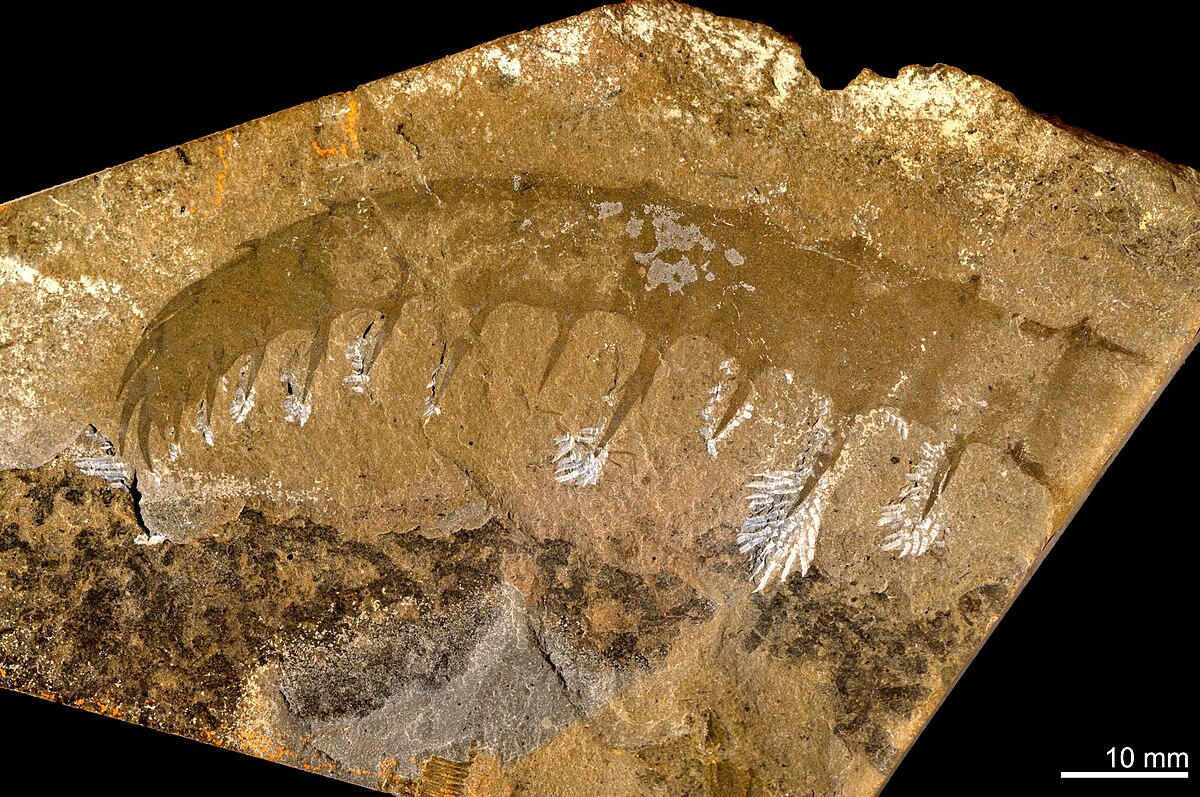

– The study involved 3D reconstructions and biomechanical modeling using well-preserved fossils from the Burgess Shale

– The findings suggest that the dynamics of the Cambrian food webs were more complex than previously thought

– Anomalocaris canadensis was one of the largest marine animals at the time, living 508 million years ago during the Cambrian period

Extinct Apex Predator Likely Weaker Than Assumed, Research Says

In the fascinating world of prehistoric creatures, discoveries and insights constantly challenge our understanding of the past. One such revelation comes from recent studies on the marine animal Anomalocaris canadensis, which suggest that this extinct creature may have been weaker than initially believed. These findings shed light on the complex dynamics of the Cambrian food webs and challenge previous assumptions about the role of Anomalocaris as an apex predator.

Initially dubbed the “weird shrimp from Canada,” Anomalocaris canadensis was thought to be responsible for the scarred and crushed trilobite exoskeletons discovered in the fossil record. Paleontologists believed this fearsome creature was an apex predator, roaming the seas approximately 508 million years ago in the late Cambrian period. However, new research indicates that this marine animal may not have been as powerful as previously assumed.

Biochemical studies on the arachnid-like front “legs” of Anomalocaris canadensis have provided insight into its hunting abilities. These studies suggest that the creature was more adept at pursuing weak prey than capturing hard-shelled sea creatures. Postdoctoral researcher Russell Bicknell explains that the marine animal would have been predominantly soft and squishy, unable to process hard food effectively.

International researchers utilized 3D reconstructions and biomechanical modeling to conduct this groundbreaking study. By examining well-preserved fossils from Canada’s 508-million-year-old Burgess Shale, they could construct a virtual representation of Anomalocaris canadensis. Comparisons were drawn with modern whip scorpions and whip spiders to understand the predator’s segmented appendages. The results showed that these appendages were better suited for grabbing and manipulating soft prey, with the ability to stretch out and flex.

Finite element analysis, a modeling technique used to assess stress and strain points, further supported the notion that Anomalocaris may have been ill-equipped to catch hard prey like trilobites. The appendages would have suffered damage while attempting to grasp these creatures with hard exoskeletons. This revelation challenges the previous assumption that Anomalocaris was solely responsible for the scarred trilobite exoskeletons in the fossil record.

The implications of this study are far-reaching, indicating that the dynamics of Cambrian food webs were likely much more complex than previously thought. While Anomalocaris was undoubtedly an impressive creature, its role as an apex predator may need reconsidered. This opens up exciting avenues for further exploration into the relationships and interactions between prehistoric marine animals during the Cambrian period.

During the Cambrian period, there was a significant explosion in the diversity of life, and many major animal groups alive today emerged. At this critical juncture in Earth’s history, Anomalocaris canadensis prowled the seas, leaving its mark as one of the largest marine animals of the time. With a length of approximately 2 feet (0.6 meters), this creature inspired awe and wonder among its contemporaries.

As we continue to unravel the mysteries of the past, embracing new findings with an open mind is important. The story of Anomalocaris canadensis reminds us that our understanding of ancient ecosystems is constantly evolving. It highlights the need for ongoing research and the importance of challenging our assumptions to accurately represent the Earth’s distant past.

In conclusion, the recent research on Anomalocaris canadensis provides a fascinating glimpse into the ancient world. By utilizing advanced techniques such as 3D reconstructions and biomechanical modeling, scientists have revealed that this marine animal may have been weaker than initially believed. These findings challenge our understanding of Cambrian food webs and the role of Anomalocaris as an apex predator. As we continue to explore and study the wonders of prehistoric life, we are reminded that the story of our planet is one of constant discovery and ever-increasing complexity.