Overview

The Bornean Elephant, also known as the Borneo Pygmy Elephant, is the smallest subspecies of Asian Elephant and is native to the island of Borneo in Southeast Asia. It is distinguished by its relatively small size, large ears, long tail, and generally more docile temperament compared to other Asian Elephants. Genetic studies suggest these elephants may have been isolated from mainland populations for approximately 300,000 years, resulting in unique adaptations. They inhabit lowland tropical forests, river valleys, and occasionally agricultural landscapes adjacent to natural habitats.

These elephants are highly social, living in matriarchal herds consisting of related females and their offspring, while adult males are mostly solitary or form temporary bachelor groups. Their daily activities include foraging for grasses, fruits, bark, and other vegetation, as well as traveling long distances to find water sources. Bornean Elephants are essential ecological engineers that help shape forest structure through their feeding and movement. However, habitat loss and fragmentation have severely reduced their available range, threatening their survival.

The Bornean Elephant is considered endangered due to its small and declining population, with fewer than 1,500 individuals remaining in the wild. Major threats include deforestation, conversion of land to palm oil plantations, human–elephant conflict, and poaching. Conservation efforts focus on protecting remaining habitats, improving connectivity between forest patches, and mitigating conflict with local communities. This unique elephant population represents a critical component of Borneo’s biodiversity and cultural heritage.

Taxonomy

Kingdom

Phylum

Class

Order

Family

Genus

Species

Sub Species

Type

Current distribution:

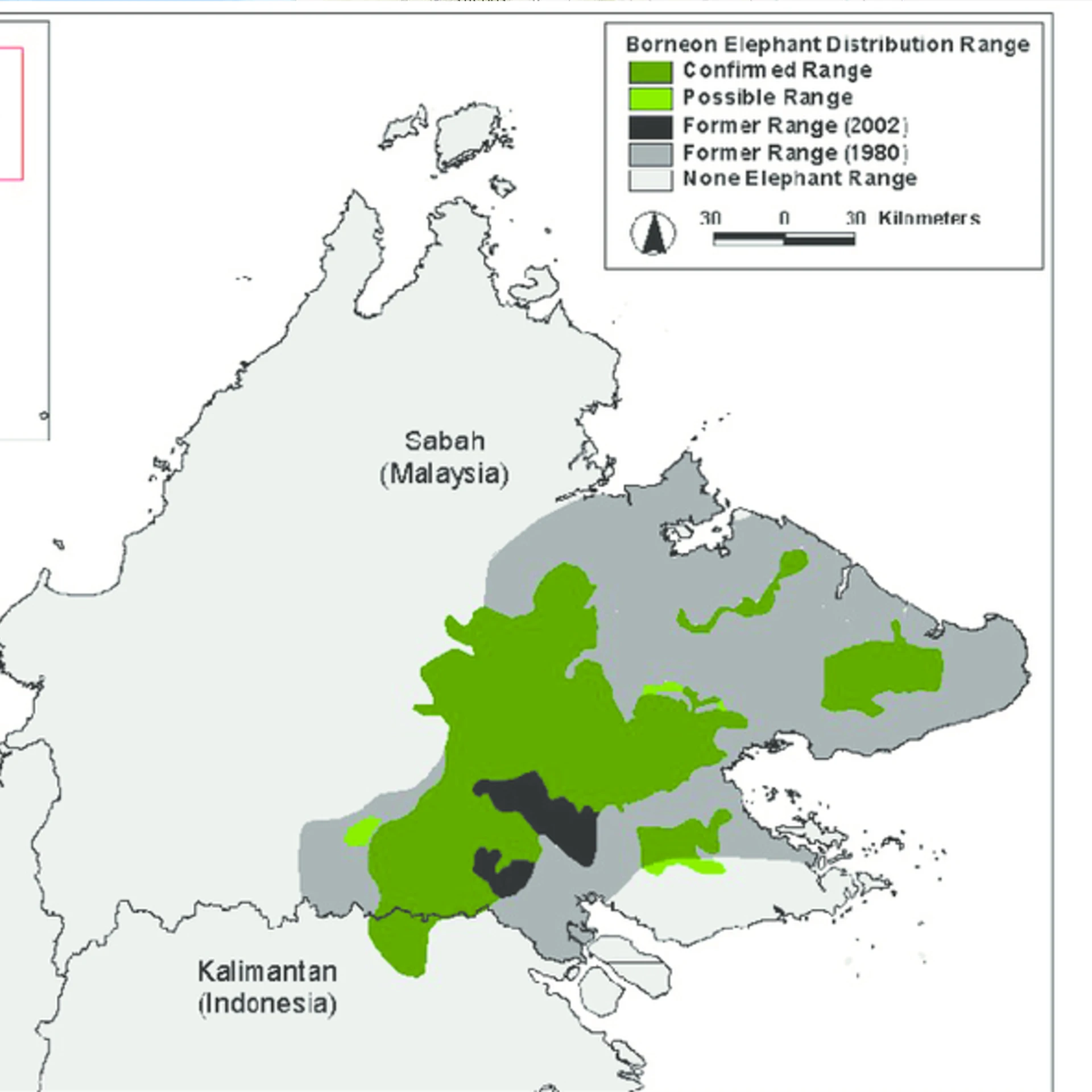

Today, Bornean Elephants occur almost exclusively in northeastern Borneo, with the largest subpopulations in Sabah’s Lower Kinabatangan floodplain, Tabin Wildlife Reserve, and central forest reserves. Smaller groups are scattered in fragmented forest patches to the west and south of these core areas. Most remaining elephants are confined to protected areas and adjacent unprotected forests threatened by deforestation and agricultural expansion. Genetic and satellite tracking studies confirm that these populations are highly isolated.

The Indonesian populations in northern Kalimantan are poorly studied and may number only a few hundred individuals. Overall, their distribution has contracted substantially in the past century. Maintaining connectivity between forest reserves is critical to prevent further genetic decline. International cooperation between Malaysia and Indonesia is crucial for securing transboundary habitat corridors.

Physical Description:

Bornean Elephants are noticeably smaller and rounder than mainland Asian Elephants, with adult females rarely exceeding 6.9 feet (2.1 meters) at the shoulder. They have relatively larger, more rounded ears and longer tails that often reach the ground. Their skin is grey, with sparse hair, and occasionally shows pale, depigmented patches behind the ears and on the trunk. Tusks are generally absent or very small in females, while males have thinner and straighter tusks compared to other subspecies.

Adults display a long, flexible trunk used for feeding, drinking, dust bathing, and tactile communication. Their legs are proportionally shorter, contributing to their compact, stocky build. The head has a twin-domed profile with a prominent indent at the top of the skull. Calves are born with a covering of fine hair and are highly dependent on their mothers and allomothers for several years.

Lifespan: Wild: ~60 Years || Captivity: ~75 Years

Weight: Male: 6,000–9,000 lbs (2,722–4,082 kg) || Female: 4,500–7,500 lbs (2,041–3,402 kg)

Length: Male: 192–216 in (488–549 cm) || Female: 168–192 in (427–488 cm)

Height: Male: 84–96 in (213–244 cm) || Female: 72–84 in (183–213 cm)

Top Speed: 25 mph (40 km/h)

Characteristic:

Native Habitat:

Bornean Elephants inhabit lowland and hill dipterocarp forests, riverine forests, and adjacent grasslands primarily in the Malaysian state of Sabah and parts of northern Kalimantan, Indonesia. They prefer habitats with abundant vegetation, permanent water sources, and minimal disturbance from human activity. Dense forests provide cover and thermal refuge, while clearings and riverbanks serve as important feeding grounds. Seasonal flooding influences their movement patterns and access to resources.

Home ranges can be extensive, sometimes exceeding 250 square miles (650 square kilometers), depending on the quality of the habitat and the degree of habitat fragmentation. Critical habitat corridors connect protected areas, enabling elephants to migrate between feeding and breeding sites. Conversion of forest to plantations and infrastructure has disrupted these movements and increased contact with humans. Conservation planning prioritizes protecting and reconnecting remaining lowland forest blocks.

Climate Zones:

Biomes:

WWF Biomes:

Biogeographical Realms:

Continents:

Countries:

Diet:

Diet & Feeding Habits:

Bornean Elephants are herbivorous generalists, consuming a wide variety of plant materials, including grasses, leaves, bamboo, fruits, bark, and cultivated crops when available. Daily foraging can last for over 18 hours and involve traveling several miles to find sufficient food and water. They often feed along riverbanks and forest clearings, which provide nutrient-rich forage and access to water. Seasonal movements are influenced by fruiting cycles and water availability during the dry season.

Their digestive system is adapted for processing large volumes of fibrous plant matter with relatively low digestive efficiency. This necessitates a high daily intake—adults can consume over 300 pounds (136 kg) of vegetation each day. Bornean Elephants also play a key role in seed dispersal through defecation, which contributes to forest regeneration. Conflict sometimes arises when elephants raid crops, leading to economic losses for farmers.

Mating Behavior:

Mating Description:

Bornean Elephants have a polygynous mating system in which mature males in musth compete for access to receptive females. Musth is a period of heightened sexual activity and aggression characterized by temporal gland secretion and urine dribbling. Females come into estrus every 3–4 years and are receptive for only a few days at a time. Courtship involves the male following the female closely, testing her reproductive status with the trunk, and occasionally vocalizing or blocking her path.

Gestation lasts approximately 19–22 months, the longest of any land mammal, resulting in a single calf weighing around 90 kilograms (200 pounds). The calf is dependent on its mother’s milk for at least two years and remains with the family herd for life. Interbirth intervals are long, which limits the reproductive potential of the population. Males disperse upon reaching adolescence and lead mostly solitary lives thereafter.

Reproduction Season:

Birth Type:

Pregnancy Duration:

Female Name:

Male Name:

Baby Name:

Social Structure Description:

Bornean Elephants live in matriarchal family units typically composed of related females and their dependent offspring. Herds may number from 5 to over 20 individuals, depending on the quality of the habitat and the availability of resources. Females cooperate in caring for calves and share information about foraging sites and water sources. Adult males leave their natal groups at adolescence and adopt solitary or bachelor lifestyles.

Communication within herds includes low-frequency rumbles, trumpeting calls, and chemical signals. Strong social bonds exist among females, who often remain together for their entire lives. Calves are cared for not only by their mothers but also by older siblings and aunts. This cooperative behavior enhances calf survival in the challenging tropical environment.

Groups:

Conservation Status:

Population Trend:

The total population of Bornean Elephants is small and fragmented, making them highly vulnerable to genetic bottlenecks and stochastic events. Surveys indicate most subpopulations number fewer than 300 individuals, with the largest concentrations in Sabah’s protected areas. Genetic diversity is declining due to isolation, and mortality from human conflict further exacerbates this trend. Long reproductive cycles and low birth rates limit the potential for rapid recovery.

Captive populations are extremely limited and are primarily held in Malaysian wildlife centers for rehabilitation and research purposes. These facilities are not yet sufficient to support large-scale captive breeding programs. Translocation efforts have been employed to mitigate conflict, but they are challenging due to logistical and ecological constraints. Without urgent habitat protection and connectivity, the risk of extinction increases significantly.

Population Threats:

Deforestation for palm oil plantations, logging, and infrastructure development has eliminated vast areas of suitable habitat. Fragmentation forces elephants into smaller ranges, increasing encounters with humans and leading to property damage and retaliatory killings. Illegal hunting for ivory, though less common in Borneo compared to Africa, remains a threat. Ingestion of agricultural chemicals and obstruction by fences and roads also contribute to mortality.

Climate change may worsen habitat degradation and disrupt food and water availability. Genetic isolation is a growing concern due to the lack of functional corridors between reserves. Crop-raiding behavior exacerbates negative perceptions among local communities. Without coordinated action, these threats will likely continue driving population decline.

Conservation Efforts:

Conservation strategies focus on securing and reconnecting critical habitat corridors to enable gene flow between fragmented subpopulations. Community-based programs offer incentives for coexistence, including compensation for crop damage and the promotion of elephant-friendly land-use practices. Satellite tracking and genetic research inform conservation planning and identify priority areas for protection. Anti-poaching patrols and improved enforcement of wildlife laws reduce direct hunting pressure.

International collaborations, including transboundary agreements between Malaysia and Indonesia, aim to secure long-term protection of habitats. NGOs and governments have established conservation areas, such as the Tabin Wildlife Reserve and the Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary. Education campaigns raise awareness of the Bornean Elephant’s ecological importance and cultural value. Continued funding and political commitment are essential to sustain these initiatives.

Additional Resources:

Fun Facts

- They are the smallest subspecies of Asian Elephant.

- Their tails are so long that they often drag on the ground.

- Bornean Elephants have more rounded ears than other Asian Elephants.

- Calves are born weighing over 200 pounds.

- Their home ranges can cover over 250 square miles.

- They can live up to 75 years in captivity.

- Genetic studies suggest they have been isolated for 300,000 years.

- They are known for their unusually gentle temperament.

- Musth males produce a strong-smelling secretion from temporal glands.

- They play a vital role in dispersing seeds that regenerate Borneo’s forests.