Overview

The Bornean Orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) is one of three species of orangutans found exclusively on the island of Borneo. It is the largest arboreal mammal, spending most of its life in trees, moving through the canopy using its long, powerful arms. This species is highly intelligent, capable of using tools, solving problems, and displaying complex emotions. Its solitary nature distinguishes it from other great apes, with males and females generally interacting only during mating.

Bornean orangutans have a highly developed social structure. Adult males establish large territories that may overlap with several females. As they mature, males develop distinctive cheek pads, called flanges, which are associated with dominance and reproductive success. They communicate using a range of vocalizations, including loud, echoing “long calls,” to establish territory and attract mates. Unlike many primates, Bornean orangutans show minimal aggression and rely on intelligence rather than brute force for survival.

This species faces severe threats from deforestation, habitat fragmentation, and illegal hunting. As their rainforest habitat is rapidly cleared for palm oil plantations and agriculture, orangutans are forced into smaller, disconnected populations. Conservation efforts focus on habitat protection, anti-poaching laws, and rehabilitation programs for orphaned orangutans. The species remains critically endangered despite these efforts due to continued habitat destruction and human activity.

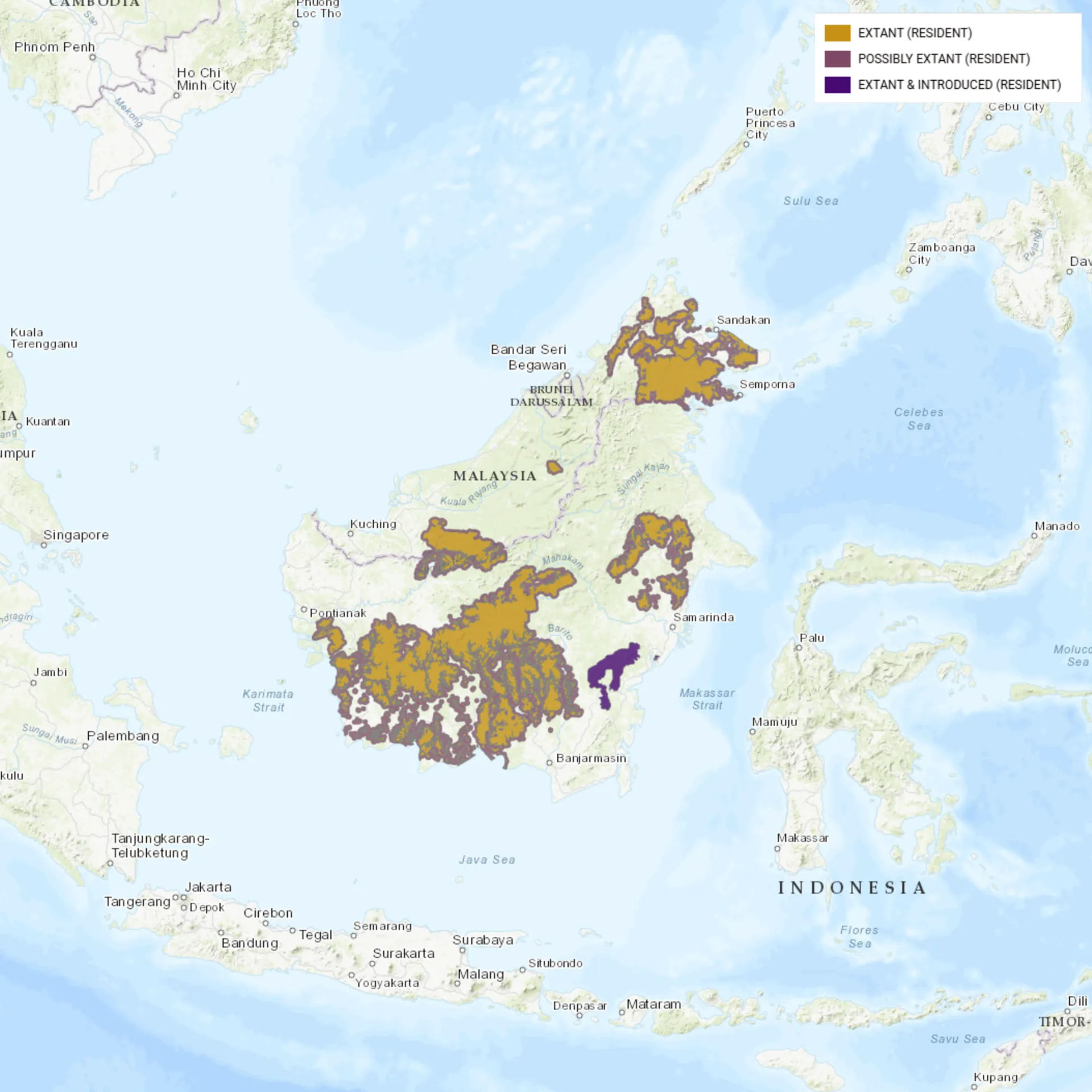

Current distribution:

Bornean orangutans are found exclusively on the island of Borneo, which is divided between Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei. The largest populations exist in the Indonesian provinces of Kalimantan and the Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak. Their distribution is highly fragmented due to deforestation, with some populations isolated in protected reserves and national parks. Key conservation areas include Tanjung Puting National Park, Gunung Palung National Park, and Sebangau National Park.

Habitat loss due to logging, palm oil plantations, and agricultural expansion continues to push orangutans into smaller forest patches. Human- wildlife conflict has increased as orangutans venture into farmland in search of food, leading to retaliatory killings. Conservation programs focus on habitat preservation and anti-poaching efforts, but the illegal pet trade remains a significant issue. Without stronger enforcement and sustainable land-use policies, Bornean orangutans face continued population decline.

Physical Description:

Bornean orangutans have long, shaggy, reddish-brown fur that provides camouflage in the dense rainforest canopy. Their long arms, which can reach up to 7 feet (2.1 meters, allow them to swing effortlessly between trees. Males develop large cheek pads, known as flanges, and a throat sac used to produce deep, resonant calls. Females are smaller and lack prominent cheek pads but have strong, muscular builds suited for climbing.

They have a highly dexterous grip, long fingers, and opposable thumbs that help them manipulate food and tools. Their feet are also adapted for grasping, making them well-suited for an arboreal lifestyle. Unlike other great apes, they have a more pronounced brow ridge and a broad, flat face with deep-set eyes. Bornean orangutans exhibit sexual dimorphism, with males significantly larger and heavier than females.

Lifespan: Wild: ~45 Years || Captivity: ~55 Years

Weight: Male: 110–220 lbs (50–100 kg) || Female: 66–110 lbs (30–50 kg)

Length: Male: 47–60 in (119–152 cm) || Female: 39–48 in (99–122 cm)

Height: Male: 45–54 in (114–137 cm) || Female: 36–42 in (91–107 cm)

Top Speed: 3.7 mph (6 km/h) (Ground)

Characteristic:

Native Habitat:

Bornean orangutans inhabit tropical and subtropical lowland rainforests, peat swamp forests, and montane forests up to 1,500 meters in elevation. They prefer dense, undisturbed forests with abundant fruiting trees that provide food and nesting sites. Unlike their Sumatran relatives, Bornean orangutans spend more time on the ground due to differences in habitat structure. Peat swamp forests are particularly important for survival, offering food availability year-round and protection from human encroachment.

They construct sleeping nests high in the trees using large leaves and branches for comfort and security each night. Though their home ranges can be extensive, they are largely solitary, with minimal overlap between males. Orangutans avoid open areas and rely on the thick canopy for protection from predators and environmental hazards. The continued destruction of Borneo’s forests threatens their long-term survival by reducing available habitat and fragmenting populations.

Climate Zones:

Biomes:

WWF Biomes:

Biogeographical Realms:

Continents:

Diet:

Diet & Feeding Habits:

Bornean orangutans are primarily frugivorous, with over 60% of their diet consisting of fruit, particularly figs. They also consume leaves, flowers, bark, insects, and occasionally small vertebrates when fruit is scarce. Their feeding habits are crucial in forest ecology as they disperse seeds over large areas, aiding plant regeneration. During food scarcity, they rely on fallback foods like tough leaves and tree bark.

They use tools like sticks to extract honey, insects, and seeds from hard-to-reach places. Orangutans chew leaves to create sponges to collect water from tree holes. Feeding behaviors vary by region, with some populations developing unique foraging techniques suited to their environment. Their slow metabolism allows them to survive on lower-quality food for extended periods if necessary.

Mating Behavior:

Mating Description:

Bornean orangutans exhibit a polygynous mating system, where dominant flanged males have priority access to females. However, unflanged males also mate opportunistically, sometimes forcing copulation in the absence of a dominant male. Mating occurs year-round, but females only give birth once every 6 to 8 years due to the long period of maternal care. Male orangutans do not participate in raising offspring, leaving all parental responsibilities to the mother.

Gestation lasts approximately 8.5 months, after which a single infant is born and remains dependent on its mother for up to 8 years. Orangutan mothers are highly protective, teaching their young essential survival skills such as foraging, climbing, and nest-building. Young orangutans often stay close to their mothers well into adolescence, learning through observation and imitation. This prolonged dependency contributes to their slow reproductive rate, making population recovery difficult.

Reproduction Season:

Birth Type:

Pregnancy Duration:

Female Name:

Male Name:

Baby Name:

Social Structure Description:

Bornean orangutans have a semi-solitary social structure, which is unusual among great apes. Adult males are highly territorial and generally avoid each other, only interacting with females for mating. Dominant flanged males use long calls to establish their presence and deter rivals, while unflanged males remain more inconspicuous and may still reproduce opportunistically. Conversely, females maintain loose social networks, often interacting with their offspring and occasionally with other females in overlapping home ranges.

Mother-offspring bonds are the strongest social relationships, with young orangutans staying with their mothers for up to eight years to learn essential survival skills. Juveniles may engage in playful interactions with other young orangutans but eventually adopt a more independent lifestyle as they mature. Unlike chimpanzees or bonobos, orangutans do not form large social groups, relying instead on their intelligence and memory to navigate their environment. Their semi-solitary nature helps reduce competition for food in the dense rainforest, where resources can be widely dispersed.

Groups:

Conservation Status:

Population Trend:

The Bornean orangutan population has experienced a dramatic decline due to habitat destruction, poaching, and human encroachment. Estimates suggest that the wild population has decreased by over 50% in the last 60 years, with around 104,700 individuals remaining. Their distribution is highly fragmented, with populations confined to protected areas and isolated forest patches. The slow reproductive rate of orangutans, with females giving birth only once every 6 to 8 years, makes population recovery especially challenging.

Captive populations exist in zoos, rehabilitation centers, and sanctuaries, where conservationists work to reintroduce rehabilitated individuals into the wild. However, reintroduction efforts are complex, as orangutans require large, undisturbed habitats to survive. Conservation programs focus on habitat protection, anti-poaching laws, and sustainable forestry practices to prevent further declines. Despite these efforts, illegal hunting and habitat destruction remain persistent threats, keeping the species at a critically endangered status.

Population Threats:

The primary threat to the Bornean orangutan population is habitat destruction due to deforestation for palm oil plantations, logging, and agricultural expansion. Large-scale deforestation has resulted in severe habitat fragmentation, forcing orangutans into smaller, isolated populations with reduced genetic diversity. The loss of continuous forest cover makes it difficult for orangutans to find food, shelter, and mates, increasing their vulnerability. Infrastructure development, including roads and settlements, further fragments their habitat and increases human- wildlife conflict.

Illegal hunting and poaching for the pet trade also contribute to population declines, with young orangutans often taken from the wild after their mothers are killed. Some are also hunted for bushmeat in certain regions despite legal protections. Human- wildlife conflicts arise when orangutans enter farmlands in search of food, leading to retaliatory killings by farmers and plantation workers. Climate change exacerbates these threats by altering fruiting patterns and increasing the frequency of forest fires, further reducing available habitat.

Conservation Efforts:

Numerous conservation organizations and government initiatives are working to protect Bornean orangutans through habitat conservation, anti-poaching enforcement, and rehabilitation programs. National parks and reserves, such as Tanjung Puting and Sebangau National Park, provide protected areas for wild populations. Several conservation groups, including the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation and the Orangutan Foundation International, rescue and rehabilitate orphaned orangutans for reintroduction into the wild. Conservationists are also working to establish wildlife corridors to reconnect fragmented populations and promote genetic diversity.

Anti-poaching laws and stricter enforcement aim to reduce illegal hunting and the pet trade, though challenges remain due to weak regulations and corruption. Sustainable palm oil certification programs, such as those led by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), encourage companies to adopt deforestation-free practices. Education and awareness campaigns in local communities help promote coexistence and reduce human-orangutan conflicts. Despite ongoing efforts, habitat destruction and illegal activities threaten the species, requiring stronger global conservation commitments.

Additional Resources:

Fun Facts

- Bornean orangutans have the longest interbirth interval of any land mammal, at 6–8 years.

- Their name means “person of the forest” in Malay and Indonesian.

- They use large leaves as umbrellas to protect themselves from rain.

- Orangutans are the most arboreal of the great apes, rarely descending to the ground.

- They have incredible memory, remembering the locations of fruiting trees over vast distances.

- Unlike other apes, they are primarily solitary rather than living in large groups.

- Some populations have been observed using tools like sticks to extract food.

- Bornean orangutans have unique fingerprints, just like humans.

- They can live over 50 years in captivity, significantly longer than in the wild.

- They play a crucial role in maintaining forest biodiversity by dispersing seeds.