Overview

The Brazilian tapir (Tapirus terrestris), also known as the South American tapir, is a large herbivorous mammal native to the tropical forests of South America. It is the largest land mammal in the Amazon Rainforest, characterized by its distinctive prehensile snout, which it uses for grasping leaves, fruits, and aquatic vegetation. As a strong swimmer, it often inhabits areas near rivers and lakes, where it can escape predators and regulate its body temperature. This species plays a crucial role in forest ecosystems by dispersing seeds and contributing to plant regeneration and biodiversity.

Brazilian tapirs are generally solitary, except during mating or when mothers care for their young. They are most active at night (nocturnal) or during twilight hours (crepuscular), using their excellent sense of smell and hearing to navigate dense forests. When threatened, they rely on their ability to run swiftly through thick vegetation or take refuge in water. Although usually shy and non-aggressive, they can defend themselves with powerful bites if cornered by predators.

Habitat destruction, hunting, and competition with livestock have led to population declines in some regions. While the species remains relatively widespread, deforestation for agriculture and urban expansion continues to fragment its habitat. Conservation efforts focus on habitat protection, anti-poaching laws, and captive breeding programs to maintain genetic diversity. Despite ongoing threats, the Brazilian tapir remains in many protected areas, providing hope for long-term population stability.

Taxonomy

Kingdom

Phylum

Class

Order

Family

Genus

Species

Type

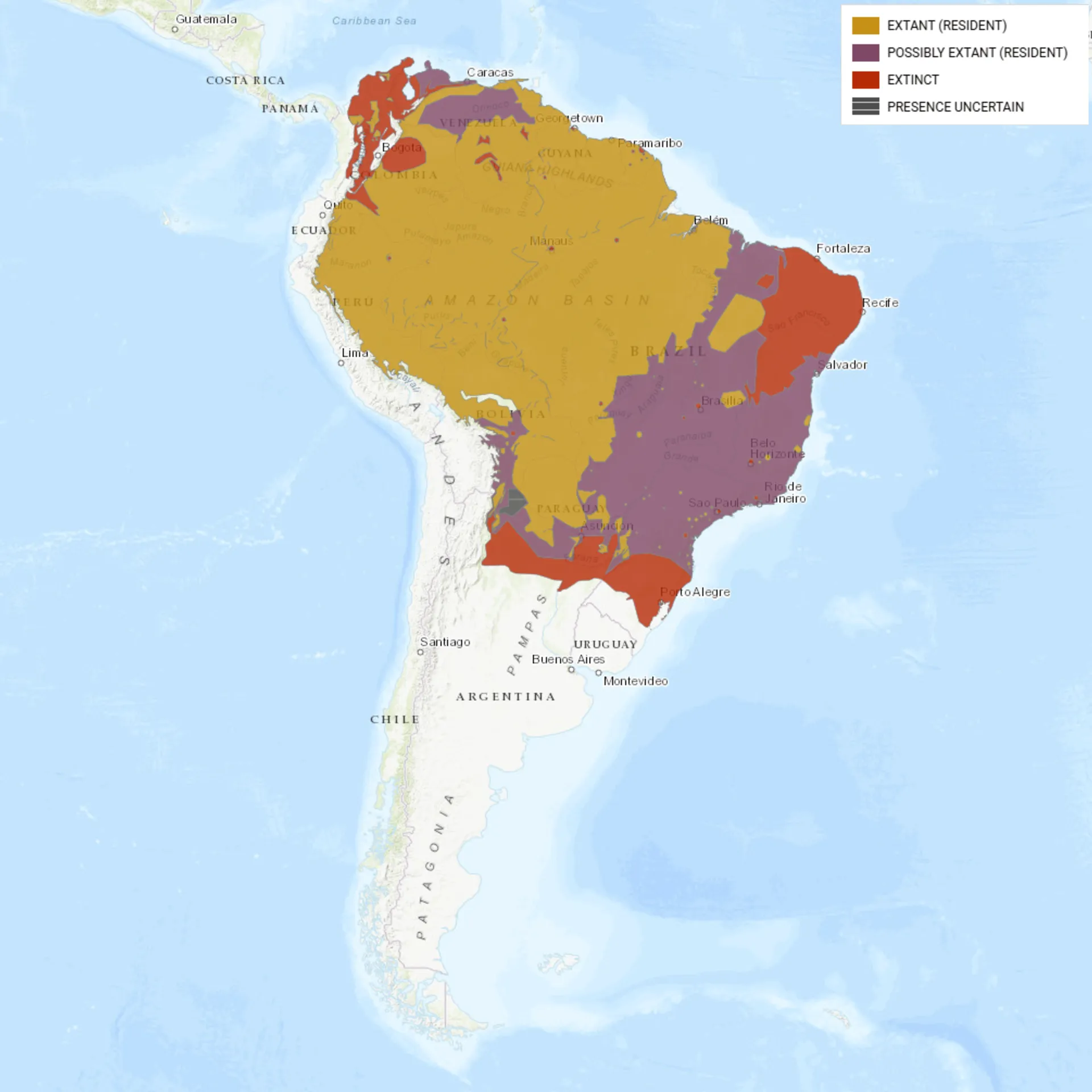

Current distribution:

The Brazilian tapir is widely distributed across South America, including Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Argentina. Its highest population densities are in the Amazon Rainforest and the Pantanal, where large, continuous forests provide sufficient resources. While the species is adaptable, habitat loss due to agriculture, logging, and urban expansion has reduced populations in some areas. Conservation programs have helped maintain populations in protected reserves and national parks.

In regions with severe deforestation, tapir populations are becoming increasingly fragmented, leading to genetic isolation. Poaching and hunting for meat further threaten some populations, despite legal protections in many countries. Efforts to establish wildlife corridors aim to reconnect isolated populations, allowing for gene flow and healthier population dynamics. While relatively widespread, continued habitat destruction could push the species toward a more threatened status.

Physical Description:

The Brazilian tapir has a robust, barrel-shaped body covered in short, dark brown to grayish-brown fur. It possesses a distinctive, flexible prehensile snout that resembles a short trunk, which it uses to grasp leaves, fruits, and branches. Its small, rounded ears have white edges, providing a contrast against its darker fur. The eyes are relatively small, adapted for low-light vision, while its strong limbs and broad hooves allow it to move efficiently through muddy terrain and dense vegetation.

Newborn tapirs are strikingly covered in reddish-brown fur with white spots and stripes, providing camouflage in their forest habitat. These markings fade as they mature, typically disappearing by six months of age. Adults grow substantially, with males and females appearing similar, though females are generally slightly larger. The thick and tough skin protects against insect bites and minor injuries from branches and undergrowth.

Lifespan: Wild: ~25 Years || Captivity: ~35 Years

Weight: Male & Female: 330–550 lbs (150–250 kg)

Length: Male & Female: 67–83 in (170–210 cm)

Height: Male & Female: 31–43 in (79–110 cm)

Top Speed: 30 mph (48 km/h)

Characteristic:

Native Habitat:

The Brazilian tapir inhabits various forested and wetland environments, including tropical rainforests, flooded grasslands, and savannas. It is most commonly found in the Amazon Rainforest but also occurs in the Atlantic Forest, Pantanal, and parts of the Cerrado. These habitats provide dense vegetation, water sources, and abundant food, essential for survival. Tapirs prefer areas with ample tree cover, where they can remain hidden from predators during the day.

They rely heavily on water bodies such as rivers, lakes, and swamps, using them to escape predators and cool off in hot climates. Their ability to swim and dive allows them to access food sources other terrestrial herbivores cannot reach. They are also found in secondary forests, demonstrating some adaptability to disturbed environments. However, large-scale deforestation and habitat fragmentation continue to threaten their long-term survival.

Climate Zones:

Biogeographical Realms:

Continents:

Diet:

Diet & Feeding Habits:

The Brazilian tapir is an herbivore that feeds primarily on leaves, fruits, bark, and aquatic vegetation. Its prehensile snout functions like a small trunk, allowing it to grasp food from trees and shrubs. The tapir plays a key ecological role as a seed disperser, consuming fruits and excreting seeds throughout the forest, which aids in plant regeneration. Tapirs also consume mineral-rich soil, which helps supplement their diet with essential nutrients.

They are selective feeders, choosing plants based on seasonal availability and nutritional content. Most of their feeding occurs at night or early morning and evening to avoid predators and excessive heat. In areas near water, they often forage for aquatic plants and will submerge themselves to access submerged vegetation. Their slow digestion allows them to extract maximum nutrients from fibrous plant material, supporting their large body size.

Mating Behavior:

Mating Description:

Brazilian tapirs have a polygynous mating system, where dominant males mate with multiple females within their home range. Mating typically occurs during the rainy season when food is abundant, increasing the chances of successful reproduction. Courtship involves vocalizations, scent marking, and playful chasing behaviors before copulation. Males do not participate in parental care, leaving the female to raise the offspring alone.

Gestation lasts approximately 13 months, after which a single calf is born, though twins are rare. The calf is born with a reddish-brown coat covered in white stripes and spots, which provide camouflage in dense vegetation. It remains close to its mother for up to a year, learning foraging and survival skills before becoming independent. Due to the long gestation and maternal care period, female tapirs reproduce only every two to three years.

Reproduction Season:

Birth Type:

Pregnancy Duration:

Female Name:

Male Name:

Baby Name:

Social Structure Description:

The Brazilian tapir is primarily a solitary animal, with individuals maintaining large home ranges that overlap with others. They are most active at night and during twilight hours, relying on their keen sense of smell and hearing to navigate their environment. While they generally avoid direct interactions, they may tolerate each other at shared water sources or feeding areas. The only strong social bond occurs between a mother and her calf, as she provides care and protection for up to a year before the young becomes independent.

Males and females only come together briefly during the mating season, after which they return to their solitary lifestyles. Tapirs communicate using high-pitched whistles, scent marking, and body language to signal their presence or deter rivals. While they are typically peaceful, they can become aggressive if threatened, using their strong jaws and sharp teeth for defense. Their solitary nature helps reduce competition for food and allows them to move quietly through dense forests without attracting predators.

Groups:

Conservation Status:

Population Trend:

The Brazilian tapir population is estimated to be around 100,000 individuals in the wild, but numbers vary significantly across its range. It remains relatively abundant in remote regions of the Amazon Rainforest and the Pantanal, where large, continuous forests provide sufficient resources. However, populations have become highly fragmented in areas with heavy deforestation, such as the Atlantic Forest and parts of the Cerrado. This isolation increases the risk of genetic bottlenecks and reduces the species’ ability to recover from environmental changes or hunting pressures.

Although still widespread, the species is experiencing a steady decline due to habitat loss, hunting, and competition with livestock for resources. Tapirs are slow breeders, with females only giving birth once every two to three years, making it difficult for populations to rebound quickly. In some regions, hunting for meat and sport has drastically reduced numbers, despite legal protections in many countries. Conservation programs focused on habitat preservation, anti-poaching efforts, and wildlife corridors are critical for maintaining stable populations and preventing further declines.

Population Threats:

The biggest threat to the Brazilian tapir is habitat destruction due to deforestation for agriculture, logging, and urban expansion. Large-scale clearing of forests, particularly in the Amazon, Atlantic Forest, and Cerrado, has led to significant habitat fragmentation, isolating populations and reducing their access to food and water sources. This fragmentation increases the risk of genetic bottlenecks and makes tapirs more vulnerable to environmental changes. Infrastructure development, such as roads and highways, also disrupts their habitat and increases the likelihood of vehicle collisions.

Hunting is another major threat, as tapirs are often targeted for their meat and hide, despite legal protections in many countries. In some regions, they are hunted as pests due to perceived competition with livestock for resources. Climate change also alters rainfall patterns and water availability, potentially impacting their food supply and preferred wetland habitats. Conservation efforts are essential to prevent further population declines as human activities continue encroaching on their natural range.

Conservation Efforts:

Efforts to protect the Brazilian tapir focus primarily on habitat conservation, anti-poaching measures, and research initiatives. Protected areas, such as national parks and wildlife reserves in the Amazon, Pantanal, and Atlantic Forest, serve as crucial strongholds for tapir populations. Conservation organizations work to establish and maintain wildlife corridors to reconnect fragmented habitats, allowing for gene flow between isolated populations. Reforestation projects in degraded areas also help restore lost habitat, ensuring long-term survival for the species.

Anti-hunting laws and stricter enforcement aim to reduce poaching, though illegal hunting remains a concern in some regions. Conservation groups conduct public awareness campaigns to educate local communities about the tapir’s ecological importance as a seed disperser. Research programs monitor population trends, health, and genetic diversity to inform conservation strategies. Captive breeding programs in zoos and wildlife centers contribute to the species’ long-term conservation, though maintaining wild populations remains the top priority.

Additional Resources:

Fun Facts

- The Brazilian tapir is an excellent swimmer and can dive underwater to escape predators.

- Its flexible snout functions like an elephant’s trunk, helping it grasp leaves and fruits.

- Calves are born with white-spotted coats that fade after six months.

- Tapirs communicate using high-pitched whistles and scent markings.

- They play a vital role in forest ecosystems by dispersing seeds.

- Their closest relatives are horses and rhinos, not pigs.

- They can consume toxic plants that are harmful to other animals.

- Despite their bulky appearance, tapirs can run fast to escape predators.

- They often take mud baths to cool down and protect their skin from parasites.

- Tapirs have been around for over 20 million years, which makes them fossils.