Overview

The takin (Budorcas taxicolor) is a large, muscular, ungulate native to the mountainous regions of the Eastern Himalayas and neighboring areas of Asia. Often compared to a goat or an antelope, it is a member of the Bovidae family and represents a unique evolutionary lineage. Takins are well-adapted to rugged terrain and high altitudes, where they graze on various vegetation, including grasses, shrubs, and mosses. Their distinct appearance and elusive behavior have made them icons of their native mountain ecosystems, often called “goat-antelopes.”

Takins are known for their thick, golden or brownish coat, which provides insulation against the cold temperatures of their alpine habitat. Their powerful, stocky bodies are supported by strong legs with large, cleft hooves designed for climbing rocky slopes and navigating uneven terrain. These herbivores typically move in herds that vary in size depending on the season, with larger groups forming during the summer. Despite their robust build, takins are surprisingly agile and can easily traverse steep mountainsides.

The takin is Bhutan’s national animal and has cultural and ecological significance across its range. However, it is classified as a vulnerable species due to habitat loss, poaching, and competition with livestock. Conservation initiatives have focused on protecting its natural habitat and curbing illegal hunting. Because takins primarily inhabit remote areas, they are difficult to study, and much of their ecology and behavior remain relatively unknown.

Taxonomy

Kingdom

Phylum

Class

Order

Family

Genus

Species

Type

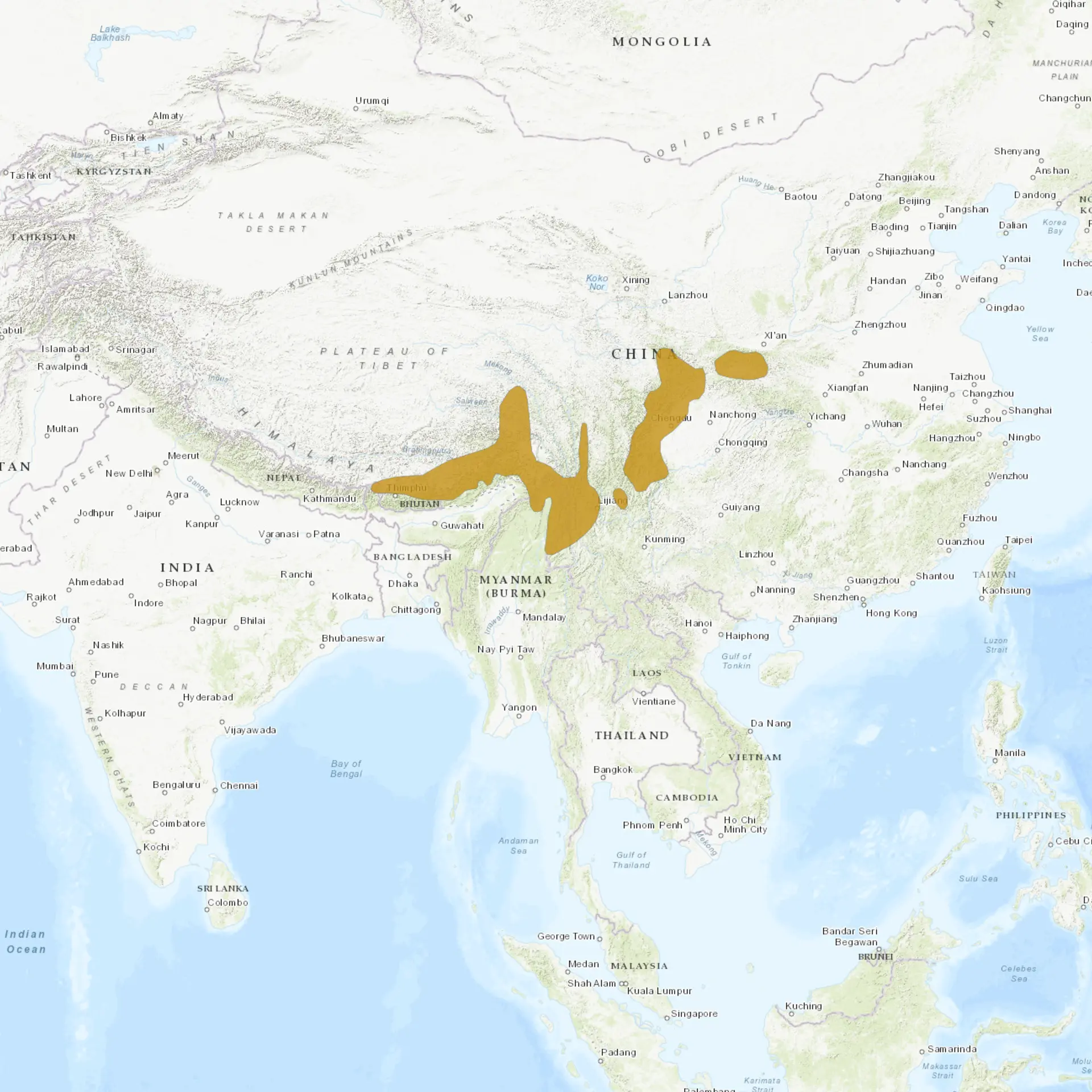

Current distribution:

The Takin's distribution is fragmented across the eastern Himalayas, with populations primarily found in Bhutan, China, India, and Myanmar. While some regions report stable or even increasing populations due to effective conservation measures, others continue to see declines because of ongoing habitat loss and poaching. Establishing transboundary protected areas and strengthening wildlife laws have been key to the conservation success stories. Continuous monitoring and research are essential to understanding the dynamics of Takin populations and adapting conservation strategies to changing environmental conditions.

Efforts to enhance habitat connectivity and to implement community-based conservation programs are underway, aiming to secure the long-term survival of the Takin. These initiatives benefit the Takin and the rich biodiversity of the Himalayan region, underscoring the species' role as an umbrella species for conservation. International cooperation and the involvement of local communities are crucial for addressing the challenges Takins face and promoting sustainable coexistence. Protecting the Takin and its habitat is a priority for conservation organizations and governments in the region, reflecting the species' cultural and ecological significance.

Physical Description:

Takins are characterized by their muscular build and large size, with adults typically reaching lengths of 170 to 220 centimeters (67 to 87 inches) and standing about 100 to 130 centimeters (39 to 51 inches) at the shoulder. Their weight can vary significantly, with some individuals weighing up to 350 kilograms (770 pounds). The thick, woolly coat that covers their body is an adaptation to the cold, damp environments they inhabit, with coloration that provides camouflage against the rocky and forested landscapes. Both males and females possess stout, arched horns that can grow up to 64 centimeters (25 inches) long, used for defense and dominance within the herd.

The Takin’s face is marked by a distinctive Roman nose and wide-set eyes, giving them an almost mythical appearance. Their hooves are split and designed to grip their mountainous habitats’ slippery, uneven surfaces, aiding their mobility across steep terrains. The dense fur and skin secretions help to repel water and parasites, contributing to their rugged durability in harsh climates. The variation in physical characteristics across subspecies reflects the diverse environments in which Takins are found, from dense bamboo forests to alpine meadows.

Lifespan: Wild: ~15 Years || Captivity: ~20 Years

Weight: Male & Female: 550 to 770 lbs (250 to 350 kg)

Length: Male & Female: 67 to 87 in (170 to 220 cm)

Height: Male & Female: 45 to 55 in (115 to 140 cm)

Top Speed: 22 mph (35 km/h)

Characteristic:

Native Habitat:

Takins inhabit the eastern Himalayas’ forested valleys and rocky, mountainous regions, ranging from northwest India through Bhutan, China, into northern Myanmar. They are adapted to a wide range of elevations, typically from 1,000 to 4,500 meters (3,280 to 14,760 feet), where they experience various climate conditions, from warm and humid summers to cold, snowy winters. The dense forests and bamboo thickets provide shelter and abundant food sources, while the rugged terrain offers protection from predators. The preservation of these habitats is critical for the survival of the Takin, as they rely on the availability of natural resources and undisturbed areas for feeding, breeding, and seasonal migrations.

The fragmentation of Takin habitats due to deforestation, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure development poses significant challenges to their conservation. Protected areas and wildlife reserves have become essential sanctuaries for Takins, allowing them to roam freely and maintain their natural behaviors. Efforts to restore and connect fragmented habitats are crucial for facilitating their seasonal movements and ensuring genetic diversity. The Takin’s dependence on these specific environments highlights the importance of comprehensive conservation strategies that address habitat protection and management.

Climate Zones:

Biogeographical Realms:

Continents:

Diet:

Diet & Feeding Habits:

The diet of the Takin consists mainly of leaves, shoots, and grasses, with a preference for bamboo leaves where available. They are browsers and grazers, using their flexible lips and tongue to strip leaves from branches and to select the most nutritious parts of plants. In the winter, when vegetation is scarce, they may descend to lower altitudes to find food, sometimes entering agricultural areas and causing conflicts with farmers. Their four-chambered stomach facilitates their ability to digest a wide variety of plant materials, which allows for efficient fermentation and nutrient extraction.

Takins are known to visit salt licks and mineral-rich waters, which supplement their diet with necessary minerals not readily available in their plant-based diet. These excursions are crucial to their social behavior and health, often leading to temporary aggregations of individuals from different herds. The seasonal migration of Takins in search of food and minerals illustrates their adaptability and the critical need for connected habitats that support their natural behaviors. Conservation efforts aim to protect these migration routes and feeding areas to ensure the sustainability of Takin populations.

Mating Behavior:

Mating Description:

Takin mating season occurs in late spring to early summer when males compete for access to females through displays of strength and vocalizations. Dominant males may gather harems of females, which they defend from other suitors. After mating, females undergo a gestation period of about seven to eight months, culminating in the birth of usually a single calf in late winter or early spring. The mother provides all care for the calf, protecting it from predators and teaching it to forage until it is weaned and becomes more independent.

Calves are born well-developed and can walk and follow their mothers within a day of birth, adapting to their predator-rich environment. The social structure of the herd provides additional protection for calves, with group members alert to potential threats. The reproductive cycle of the Takin, including gestation and calf rearing, is closely tied to the seasonal availability of food and the need for shelter during the colder months. Conservation efforts that protect critical breeding and calving areas are essential for Takin populations’ continued health and growth.

Reproduction Season:

Birth Type:

Pregnancy Duration:

Female Name:

Male Name:

Baby Name:

Social Structure Description:

Takins are social animals that form herds of various sizes, from small family groups to larger aggregations, especially in winter when food is scarce. Within these herds, a hierarchy influences access to resources and mating opportunities. Herd composition can change seasonally, with males forming bachelor groups outside the breeding season. The social bonds within herds play a crucial role in their survival, offering protection against predators and facilitating the sharing of knowledge, such as the locations of food and salt licks.

Strong social structures enhance the resilience of Takin populations, allowing them to navigate the challenges of their environment more effectively. Calves benefit from the protection and social learning opportunities the herd provides, gaining the skills needed for independence. The dynamics of Takin social structures are complex and can be influenced by environmental conditions, population density, and human activities. Understanding and preserving the social behavior of Takins are important aspects of their conservation, as they affect their reproduction, foraging, and overall well-being.

Groups:

Conservation Status:

Population Trend:

The Takin is currently classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List, with populations facing habitat loss, fragmentation, and hunting threats. Despite legal protections in many parts of their range, illegal poaching for meat, fur, and traditional medicine continues to impact Takin numbers. Conservation efforts have stabilized some populations, including creating protected areas and anti-poaching campaigns. However, ongoing habitat destruction and the effects of climate change necessitate continued and enhanced conservation measures.

Research into Takin ecology, behavior, and genetics is vital for effectively informing conservation strategies and managing protected areas. Community-based conservation initiatives involving local people in protecting Takins and their habitat have shown promise in reducing poaching and human-wildlife conflict. Transboundary conservation efforts are essential for preserving the Takin’s migratory routes and ensuring the connectivity of their habitats. The future of the Takin depends on the success of these conservation strategies and the commitment of governments, NGOs, and local communities to safeguard this unique species.

Population Threats:

Takins face numerous threats, including deforestation and the expansion of agricultural lands, which lead to habitat loss and fragmentation. Illegal hunting for meat and body parts used in traditional medicine poses a direct threat to their survival. Competition with domestic livestock for grazing lands can lead to reduced food availability and increased risk of disease transmission. Climate change impacts the availability of food and water sources, affecting Takin’s health and reproductive success.

Efforts to combat these threats include enforcing wildlife protection laws, promoting sustainable land-use practices, and implementing disease surveillance and management programs. Habitat restoration and the creation of wildlife corridors are crucial for enhancing habitat connectivity and supporting Takin populations. Raising public awareness about the importance of Takins and their threats is key to generating support for their conservation. Protecting the Takin requires a multi-faceted approach that addresses the immediate threats to their survival and the long-term health of their ecosystems.

Conservation Efforts:

Conservation initiatives for the Takin focus on habitat protection, establishing protected areas, and enforcing anti-poaching laws. Community engagement and education programs aim to reduce human-wildlife conflict and promote coexistence. Research and monitoring efforts provide valuable data on Takin populations, health, and habitat use, informing conservation and management decisions. International collaboration is essential for addressing transboundary conservation challenges and protecting migratory routes.

Reintroduction programs have successfully restored Takin populations to parts of their historical range, demonstrating the potential for recovery. Conservation partnerships between governments, NGOs, and local communities are crucial for implementing effective conservation strategies. Sustainable tourism initiatives can benefit local communities economically while promoting the conservation of Takins and their habitats. Through these comprehensive conservation efforts, there is hope for the future of the Takin and the preservation of the unique ecosystems they inhabit.

Additional Resources:

Fun Facts

- The Takin’s unique odor, often compared to that of musk, has earned it the nickname “gnu goat.”

- Despite their bulky appearance, takins can easily climb steep slopes and navigate rocky terrain.

- They are known to visit natural salt licks essential for their mineral intake and overall health.

- In Bhutan, the Takin is considered a national symbol and is protected as part of the country’s rich natural heritage.

- The Takin’s coat changes color with the seasons, offering camouflage against predators and the elements.

- Despite their size, Takins are surprisingly agile and can run quickly when threatened.

- Takins have been observed using their horns to strip bark from trees, indicating their strength and adaptability.

- Their social nature and vocalizations are key in maintaining herd cohesion and communicating threats.

- Takins have a strong maternal bond, with mothers fiercely protecting their young from predators.

- Establishing the Takin as a flagship species for conservation has helped raise awareness and support for protecting their habitats and biodiversity in the eastern Himalayas.