Overview

The Rough-skinned Newt (Taricha granulosa) is a North American newt known for its striking appearance and potent toxin. This amphibian is characterized by its rough, granular skin, usually dark brown or olive on its dorsal side. It contrasts sharply with the bright orange or yellow belly and underside, vivid warning coloration to potential predators. It inhabits the western coast of the United States and Canada, from Northern California to Alaska, thriving in various wet habitats, from coastal forests to inland water bodies.

Adult Rough-skinned Newts are semi-aquatic, spending time in the water for breeding and on land during other life stages. They are known for their remarkable life cycle and migration patterns, traveling long distances from their terrestrial habitats to breeding sites in ponds and slow-moving streams. The breeding season brings dramatic changes in male appearance, including smoother skin and the development of a tail fin, enhancing their swimming abilities. This species exhibits a fascinating range of behaviors, from producing toxic secretions for defense to complex mating rituals in aquatic environments.

The toxin produced by Rough-skinned Newts, tetrodotoxin, is one of the most potent toxins found in nature, protecting most predators. However, the common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis) has evolved resistance to this toxin, leading to a unique predator-prey dynamic where only the most toxic newts and the most resistant snakes survive. This evolutionary arms race highlights the complex interactions within their ecosystems and the importance of these species in studying evolutionary biology and ecology.

Taxonomy

Kingdom

Phylum

Class

Order

Family

Genus

Species

Type

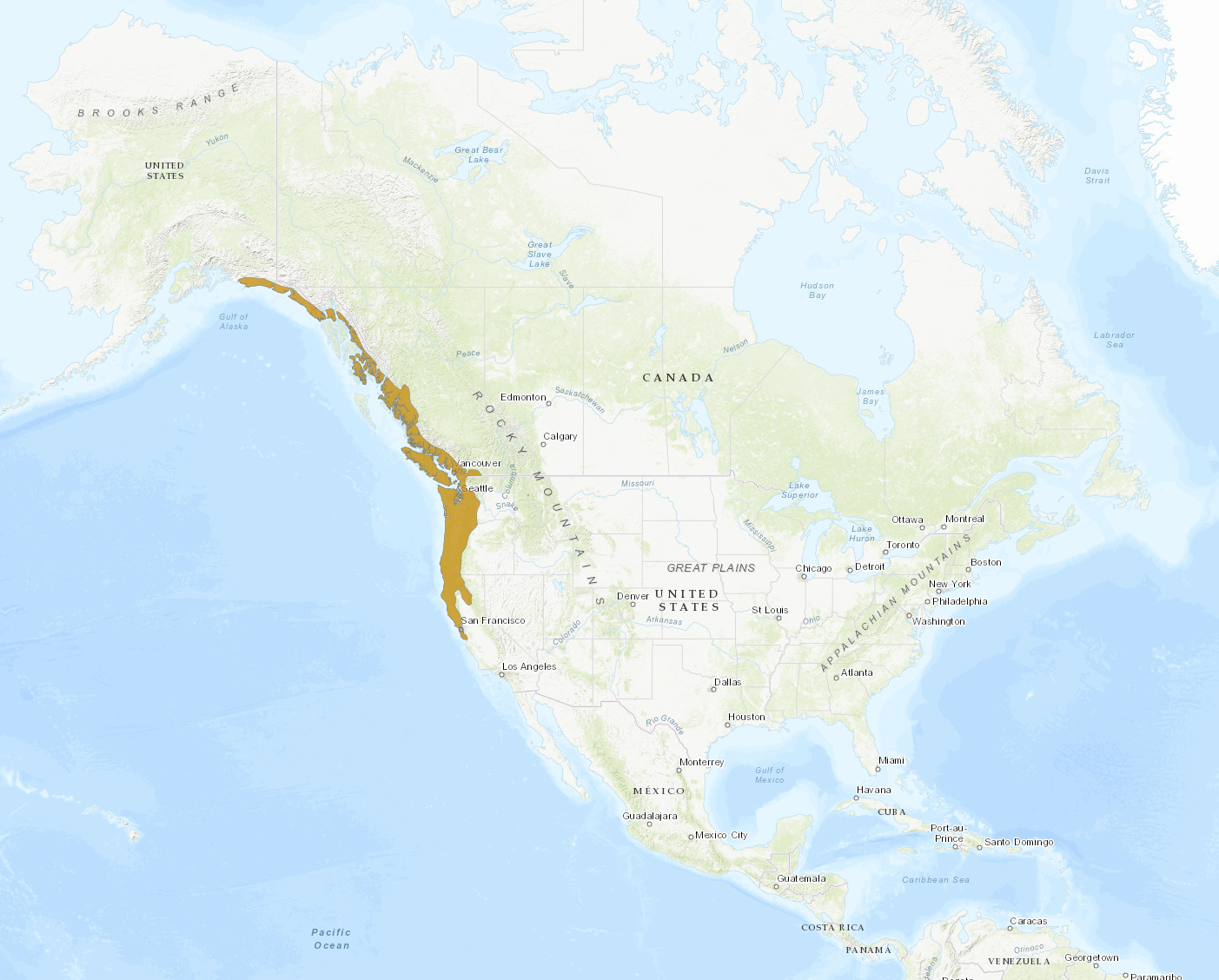

RANGE

Current distribution:

Rough-skinned Newts are found along the western coast of North America, from Northern California through Oregon, Washington, and into British Columbia, Canada. Their distribution extends to the southern coast of Alaska, making them one of the most northern-ranging newt species. Their populations are generally stable, but habitat destruction and pollution threaten their distribution.

Conservation efforts focus on protecting their natural habitats and monitoring populations to ensure continued stability. Protected areas and wildlife reserves play a key role in conserving the unique ecosystems that support Rough-skinned Newts and the diverse array of species with which they share their habitats.

Physical Description:

Rough-skinned Newts are medium-sized amphibians, with adults typically reaching 6 to 8 inches from snout to tail. Their skin is uniquely textured, appearing rough and granular, distinguishing them from other newt species with smoother skin. The dorsal side’s dark coloration serves as camouflage against the forest floor and aquatic vegetation, while the bright ventral side acts as aposematic coloration to warn predators of their toxicity.

Males and females can be differentiated by their physical characteristics, especially during the breeding season. Males develop a more streamlined body, a flattened tail for better swimming, and smoother skin, while females retain a bulkier body shape and rougher skin texture. Both sexes possess limbs well adapted for their semi-aquatic lifestyle, allowing them to navigate terrestrial and aquatic environments efficiently.

Lifespan: Wild: ~12 Years || Captivity: ~18 Years

Weight: Male & Female: 0.7-0.8 oz (22-23 g)

Length: Male & Female: 6-8 in (15.24-20.32 cm)

Characteristic:

Native Habitat:

Rough-skinned Newts are native to the Pacific Northwest of North America. They thrive in moist, forested habitats that provide ample cover and access to water. Their preferred habitats include woodland ponds, lakeshores, slow-moving streams, and wet forests. These environments offer the necessary conditions for their life cycle, including breeding, foraging, and hibernation areas.

Their terrestrial habitat is characterized by dense leaf litter and woody debris, which provides shelter from predators and extreme weather conditions. During breeding, they migrate to aquatic habitats, typically calm freshwater bodies. This migration is crucial for their reproduction, highlighting the importance of preserving their terrestrial and aquatic habitats for survival.

Climate Zones:

Biogeographical Realms:

Continents:

Countries:

Diet:

Diet & Feeding Habits:

The Rough-skinned Newt is an opportunistic feeder, consuming various prey items. Their diet consists mainly of small invertebrates in their aquatic phase, including worms, insect larvae, and crustaceans. On land, they feed on invertebrates, such as insects and slugs, which they locate using their keen sense of smell. Consuming a diverse range of prey items reflects their adaptability to different environments and the availability of food resources.

Rough-skinned newts’ feeding behavior is characterized by slow, deliberate movements, which allow them to sneak up on prey or wait for it to come within reach. Once prey is detected, they use a quick snapping motion of their jaws to capture it. This feeding strategy minimizes energy expenditure and maximizes their chances of success, which is crucial for survival in the wild.

Mating Behavior:

Mating Description:

The mating season for Rough-skinned Newts occurs in late winter to early spring, triggered by increased rainfall and rising temperatures. Males arrive at breeding sites first, establishing territories and awaiting the arrival of females. The mating process involves a complex courtship display, where the male grasps the female and rubs her with his chin to introduce pheromones, encouraging her to accept his spermatophore.

Females lay eggs individually or in small clusters on aquatic plants or submerged debris, carefully selecting sites that protect them from predators. Each female can lay up to several hundred eggs, which hatch into aquatic larvae after a few weeks. These larvae undergo metamorphosis over several months, transforming into terrestrial juveniles before eventually returning to water as adults to breed, completing their life cycle.

Reproduction Season:

Birth Type:

Pregnancy Duration:

Female Name:

Male Name:

Baby Name:

Social Structure Description:

Outside the breeding season, Rough-skinned Newts exhibit a predominantly solitary lifestyle, marking and defending individual territories within their preferred terrestrial habitats. These territories provide the newts with essential resources, including food and shelter, critical for survival during the non-breeding months. The separation into distinct territories helps minimize competition among individuals, ensuring that each has access to sufficient resources to build up energy reserves for the upcoming breeding season and the energetically demanding migration process.

However, with the onset of the breeding season, Rough-skinned Newts undergo a significant shift in behavior, migrating to and congregating in specific aquatic environments conducive to mating and egg-laying. This period saw a marked increase in social interactions among individuals as mating rituals and competition for mates became the primary focus. Transitioning from a solitary to a communal lifestyle is a fundamental aspect of their semi-aquatic lifecycle, underlining the critical role that terrestrial and aquatic habitats play in their reproductive success and overall survival. This seasonal dynamism in social structure showcases the adaptability of Rough-skinned Newts to the changing conditions of their environment.

Groups:

Conservation Status:

Population Trend:

The Rough-skinned Newt is Least Concern on the IUCN Red List, indicating general stability across its widespread range in the Pacific Northwest. This stability, however, masks localized vulnerabilities where habitat destruction due to urban expansion, agriculture, and forestry practices pose significant risks. Introducing pollutants into aquatic and terrestrial habitats, from agricultural runoff to industrial waste, further threatens the delicate balance of ecosystems these newts depend on for survival and reproduction.

In response to these threats, concerted conservation efforts are underway, aiming to mitigate the impact of human activities on the Rough-skinned Newt and similar amphibian populations. Strategies include the protection of critical habitats through the establishment of protected areas and the restoration of degraded environments. Public education programs are also vital, raising awareness about the importance of amphibians to ecosystem health and encouraging practices that reduce pollution and habitat disturbance.

Population Threats:

Habitat destruction poses a significant threat to the Rough-skinned Newt, with logging, urban expansion, and agriculture encroaching upon their terrestrial and aquatic living spaces. Such activities reduce the available habitat and fragment populations, making it difficult for newts to migrate to breeding sites and access essential resources. The loss and degradation of habitat directly impact their survival, breeding success, and the overall biodiversity of the ecosystems they inhabit.

Furthermore, pollution from agricultural runoff, industrial discharges, and other human activities contributes to the deterioration of water quality in habitats critical to the life cycle of Rough-skinned Newts. Contaminants can devastate their health, affecting larval development and reducing reproductive success. Introducing non-native species and diseases into their habitats exacerbates these challenges, leading to increased competition for already scarce resources and higher mortality rates, further threatening the delicate balance of their populations.

Conservation Efforts:

Conservation initiatives targeting Rough-skinned Newts are multifaceted, focusing on preserving their natural habitats, controlling pollution, and expanding our understanding of their ecological needs and population trends. Establishing protected areas safeguards crucial habitats from development and degradation, while wildlife corridors facilitate the essential migration and breeding activities of these amphibians by connecting fragmented habitats. This strategic approach ensures that Rough-skinned Newts have access to a mosaic of terrestrial and aquatic environments necessary for their life cycle, from breeding waters to terrestrial foraging grounds.

Furthermore, environmental regulations play a pivotal role in mitigating the impacts of human activity, specifically targeting pollution reduction and managing agricultural practices to maintain the integrity of water bodies. Such regulatory measures are vital for minimizing the infiltration of harmful substances into the ecosystems Rough-skinned Newts inhabit. Complementing these efforts, public education and outreach programs are crucial in fostering a societal appreciation for amphibians and their roles in maintaining ecosystem health. These programs aim to inspire community involvement in conservation actions, emphasizing sustainable practices that protect amphibian populations and their habitats.

Additional Resources:

Fun Facts

- Rough-skinned Newts have enough toxins to kill many animals and even humans if ingested.

- Their bright belly coloration is an example of aposematic coloration, warning predators of their toxicity.

- The evolutionary arms race between Rough-skinned Newts and garter snakes is a classic example of coevolution.

- Newts can regenerate lost limbs, eyes, spinal cords, hearts, intestines, and upper and lower jaws.

- The migration journey to breeding sites can be several kilometers long, an impressive feat for such a small amphibian.

- Rough-skinned Newts can live for over a decade, a long lifespan for an amphibian.

- Their larvae are fully aquatic and breathe through gills before undergoing metamorphosis to become terrestrial juveniles.

- Despite their toxicity, Rough-skinned Newts are preyed upon by a few specialized predators, such as the garter snake.

- They have been known to play dead when threatened, curling up and exposing their bright underbelly.

- The scientific name “granulosa” refers to the granular texture of their skin.