Overview

The North American beaver is a large, semi-aquatic rodent renowned for its ability to modify ecosystems by constructing dams and lodges. Found across much of North America, it inhabits freshwater environments such as rivers, streams, ponds, and lakes, where it uses branches, mud, and vegetation to create its iconic dams and underwater homes. These engineering feats are crucial for maintaining wetland ecosystems, as they help regulate water flow, reduce erosion, and provide habitats for numerous other species. Beavers are primarily nocturnal, spending their nights felling trees, gathering food, and maintaining their dams and lodges.

Beavers are herbivores, feeding on bark, twigs, leaves, and aquatic vegetation. They are well adapted to their semi-aquatic lifestyle, with webbed hind feet for swimming, a flat, paddle-shaped tail for propulsion and balance, and sharp incisors capable of cutting through wood. These social animals live in family groups, or colonies, which consist of a monogamous pair, their offspring, and juveniles from the previous year. The North American beaver is a keystone species, meaning its activities disproportionately impact its environment, creating habitats that support a wide range of biodiversity.

Once heavily hunted for its fur and castoreum, a secretion used in perfumes and medicines, the North American beaver was nearly extinct in the 19th century. Thanks to conservation efforts and legal protections, beaver populations have recovered in many areas and now play a vital role in wetland restoration and water management. Despite their comeback, beavers face ongoing threats from habitat loss, climate change, and human-wildlife conflict, particularly in areas where their dam-building activities conflict with human infrastructure.

Taxonomy

Kingdom

Phylum

Class

Order

Family

Genus

Species

Type

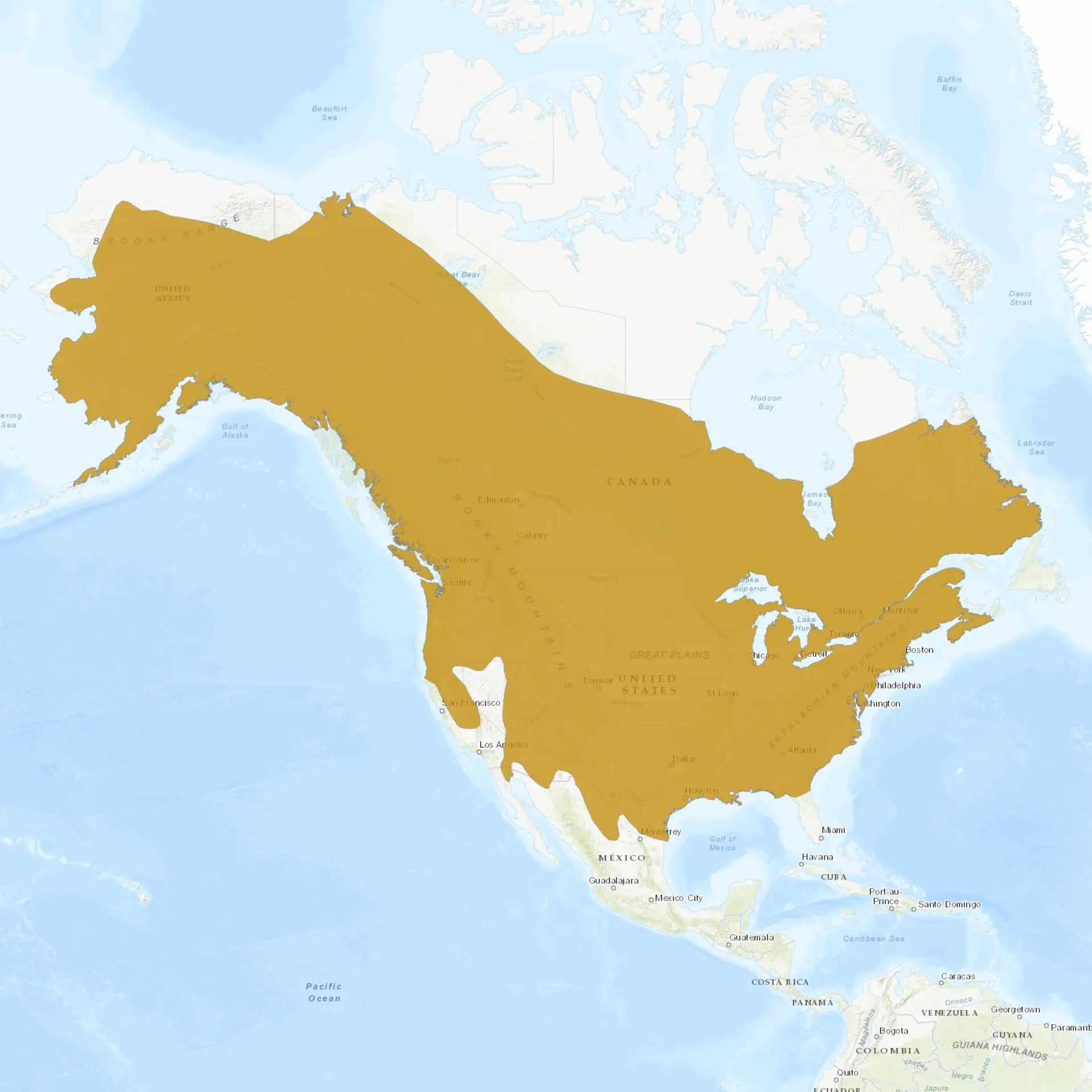

Current distribution:

The North American beaver is widely distributed across most of the United States, Canada, and northern Mexico. It is particularly abundant in the boreal forests of Canada and the northern United States, where suitable habitats are plentiful. Beavers are also found in the southeastern United States, including areas like the Mississippi Delta and arid regions where rivers and streams provide the necessary water for their activities. Their range has expanded in some areas due to conservation efforts and habitat restoration.

While beaver populations have recovered much of their historical range, localized declines occur in areas with significant habitat loss or heavy human-wildlife conflict. Urban development, agriculture, and water management projects can restrict beavers' ability to establish dams and lodges. Nevertheless, their adaptability and conservation protections have allowed them to thrive in many parts of North America. In some regions, they have even been reintroduced to restore wetlands and improve water quality.

Physical Description:

The North American beaver is the largest rodent in North America, characterized by its robust body, webbed hind feet, and distinctive flat, scaly tail. Adults typically measure 30 to 40 inches (76 to 102 cm) in length, including the tail, and weigh between 35 and 65 pounds (16 to 30 kg). Their dense, waterproof fur ranges from dark brown to reddish-brown, providing insulation and protection in cold water. Beavers have large, orange incisors coated with iron, which makes them exceptionally strong for cutting through wood and bark.

Their eyes are equipped with a nictitating membrane, or transparent third eyelid, which allows them to see underwater. At the same time, their nostrils and ears can close to prevent water from entering during dives. Their front paws are dexterous and used for carrying mud, vegetation, and branches, while the webbed hind feet are specialized for swimming. The flat tail serves multiple functions, including a rudder while swimming, standing upright support, and a warning device when slapped against water to signal danger. Beavers’ stout bodies and specialized adaptations suit their semi-aquatic environment well.

Lifespan: Wild: ~10 Years || Captivity: ~20 Years

Weight: Male: 44–60 lbs (20–27 kg) || Female: 40–55 lbs (18–25 kg)

Length: Male: 29–35 in (73.7–89 cm) || Female: 28–33 in (71.1–83.8 cm)

Height: Male: 12–15 in (30.5–38 cm) || Female: 11–14 in (28–35.6 cm)

Top Speed: 6 mph (9.7 km/h)

Characteristic:

Native Habitat:

The North American beaver is found in freshwater habitats across the country, including rivers, streams, ponds, lakes, and wetlands. It prefers areas with slow-moving water and abundant vegetation, particularly tree species like aspen, willow, and birch, which provide food and building materials. Beavers construct dams to create ponds, ensuring that their lodges remain surrounded by water to protect them from predators. These ponds also provide a stable environment for aquatic vegetation, which forms a significant part of their diet.

Beavers are highly adaptable and can inhabit a range of climates, from the boreal forests of Canada to the temperate woodlands of the United States and even arid regions with sufficient water sources. They modify their habitats extensively, creating wetland ecosystems that support a variety of plant and animal species. Their dams regulate water flow, prevent erosion, and recharge groundwater, making them essential for maintaining healthy freshwater ecosystems. Despite their adaptability, beavers are most successful in areas with ample water and access to woody vegetation.

Climate Zones:

Biomes:

Biogeographical Realms:

Continents:

Countries:

Diet:

Diet & Feeding Habits:

North American beavers are herbivores, feeding primarily on trees’ inner bark, such as aspen, willow, birch, and cottonwood. In addition to bark and wood, they consume twigs, leaves, roots, and aquatic vegetation such as water lilies and cattails. Beavers use their strong incisors to fell trees and strip bark, serving as food and construction material for their dams and lodges. During the growing season, they often stockpile branches underwater near their lodges, creating a food cache that sustains them through the winter when fresh vegetation is scarce.

Beavers’ digestive systems are specially adapted to process cellulose, the main component of plant material, through a combination of gut bacteria and reingestion of partially digested material (coprophagy). This allows them to extract maximum nutrients from their fibrous diet. Their feeding habits significantly shape their environment, as tree felling and vegetation consumption create openings for new plant growth and alter water flow. While their diet is limited to plant matter, beavers play a crucial role in maintaining the health and biodiversity of wetland ecosystems through their foraging activities.

Mating Behavior:

Mating Description:

North American beavers are monogamous, forming long-term pair bonds that typically last for life. Mating occurs in the winter, usually between January and March, depending on the latitude. Females give birth in late spring after a gestation period of approximately 100 days. Litters typically consist of 2–4 kits, born fully furred and with open eyes. The kits remain in the family lodge for several weeks, and they are nursing and learning survival skills from their parents.

The family unit, or colony, consists of the monogamous pair, their current offspring, and juveniles from the previous year. At around two years, juveniles help maintain the lodge and dam and care for the newborn kits before dispersing to establish their territories. Beavers exhibit strong parental care, with both parents actively raising the young and defending the colony’s territory. This close-knit social structure contributes to the stability and success of beaver populations.

Reproduction Season:

Birth Type:

Pregnancy Duration:

Female Name:

Male Name:

Baby Name:

Social Structure Description:

North American beavers are highly social animals. They live in family groups known as colonies, which consist of a monogamous pair, their offspring, and juveniles from the previous year. Colonies typically comprise 4–8 individuals centered around a lodge and dam, which they collectively maintain. Each colony occupies a well-defined territory defended against intruders through scent marking with castoreum and occasional physical confrontations. The colony works together to gather food, repair structures, and rear young, creating a strong cooperative bond among its members.

Juveniles remain with their parents for up to two years, helping expand and maintain the family lodge before dispersing to establish their territories. Communication within the colony includes vocalizations, tail slapping, and scent marking, allowing members to coordinate activities and warn of threats. The social structure of beavers ensures their engineering projects’ success and their young’s survival. This cooperative behavior is key to their ability to transform and maintain wetland ecosystems.

Groups:

Conservation Status:

Population Trend:

The North American beaver is a conservation success story. Populations rebounded from near extinction in the 19th century due to overhunting for fur and castoreum. Legal protections, habitat restoration, and sustainable management practices have allowed their numbers to recover across much of their historical range. Current estimates suggest there are over 10–15 million beavers in North America, a significant increase from the population lows of the fur trade era. Beavers are now widely distributed and play a key role in wetland conservation and ecosystem health.

Localized population declines still occur with significant habitat loss, water pollution, or human-wildlife conflicts. In agricultural and urban areas, beavers are sometimes seen as pests due to their dam-building activities, which can flood roads, fields, or infrastructure. Conservation efforts focus on mitigating these conflicts while preserving the ecological benefits beavers provide. Their status as a keystone species highlights their importance for maintaining biodiversity and water management in their habitats.

Population Threats:

The primary threats to North American beavers include habitat destruction due to agriculture, urban development, and deforestation. These activities reduce the availability of suitable water bodies and woody vegetation necessary for dam construction and food. Human-wildlife conflicts are another significant threat, as beaver dams can flood agricultural fields, roads, and infrastructure, leading to their removal or relocation. Beavers are still hunted for their fur and castoreum in some areas, though this is regulated in most regions.

Climate change poses an additional threat by altering water availability and vegetation composition in beaver habitats. Droughts and reduced snowpack in certain regions may limit the water sources beavers depend on while rising temperatures could shift tree species distributions. Road mortality and predation by animals such as wolves, coyotes, and bears also affect populations, particularly in younger or dispersing individuals. Addressing these threats requires balanced management strategies that account for human needs and the ecological benefits beavers provide.

Conservation Efforts:

Conservation efforts for the North American beaver focus on habitat restoration, wetland conservation, and conflict mitigation. Protected areas such as national parks and wildlife reserves provide safe habitats for beavers and their associated ecosystems. Wetland restoration projects often involve reintroducing beavers to degraded landscapes, where their dam-building activities can restore water flow, reduce erosion, and support biodiversity. Public education campaigns highlight the ecological benefits of beavers, promoting coexistence and non-lethal methods for managing conflicts.

Regulated trapping ensures sustainable management of beaver populations while reducing illegal hunting pressures. In urban and agricultural areas, innovative solutions such as flow devices (beaver deceivers) prevent flooding caused by dams without removing the animals. Continued research into beavers’ ecological roles informs conservation strategies and underscores their importance as ecosystem engineers. By preserving their habitats and fostering coexistence, beavers can continue to thrive and support wetland ecosystems.

Additional Resources:

Fun Facts

- North American beavers are the second-largest rodents in the world after the capybara.

- They can hold their breath for up to 15 minutes while swimming underwater.

- Orange teeth are due to a protective layer of iron-rich enamel, making them strong enough to gnaw through hardwoods.

- Their dams can be massive, with one in Alberta, Canada, measuring over 2,800 feet (850 meters) long.

- BBeavers’ activities create wetlands that benefit hundreds of other species, including fish, amphibians, and birds.

- They use their tails to store fat for the winter and balance, swimming, and warning signals.

- Beavers are known to mate for life and exhibit strong family bonds.

- Their lodges have multiple entrances and an inner chamber above water level to keep it dry.

- Beavers have transparent eyelids, allowing them to see underwater.

- The term “busy as a beaver” comes from their tireless work ethic in building and maintaining their structures.